Summary of: Stifling Gubernatorial Secrecy: Application of Executive Privilege to State Executive Officials.

- Comparison and Analysis: Stifling Gubernatorial Secrecy: Application of Executive Privilege to State Executive Officials and United States v. Nixon, President of the United States v. United States.

- Current Issues: The validity of executive privilege ion state and federal government.

Summary

Stifling Gubernatorial Secrecy: Application of Executive Privilege to State Executive Officials discusses the validity of executive privilege in a state governmental capacity as compared to the federal exercise of the same. The article opens with a brief overview and analysis of executive privilege in the traditional sense, in that it was intended to shield sensitive executive branch communications from disclosure and the “public dissemination…which may well temper their candor”. Matthew W. Warnock, Stifling Gubernatorial Secrecy: Application of Executive Privilege to State Executive Officials, 35 Cap. U.L. Rev. 983 (2007). The hypocrisy of such a privilege is that it, innately, contradicts the democratic free flow of information. The Supreme court states that there is a strong public interest in understanding the underlying basis for our elected representatives decisions. However, it cannot be denied that the sensitivity and uniqueness of public office will occasionally call for confidentiality. This public interest in fundamental understanding for elected official’s decisions, as well as the polar desire for the necessity for un-damped opinion and executive level discussion is translated across both state and federal executive positions.

Next the article briefly discusses the two subcategories of executive privilege: the chief executive communications privilege and the deliberative process privilege. The deliberative process privilege is “the most oft-cited from of executive privilege” and has two elements. The materials the government official is denying to disclose must have been created before the deliberative process, and the materials must be deliberative in and of themselves, meaning that they must reflect “the give and take of the consultative process”. Id. The chief executive privilege is broader, and applies to documents in their entirety and covers both pre deliberative & post deliberative documents. Some state courts have “spoken of both forms of executive privilege together, thereby blurring the distinctions between them. The deliberative process is a common sense privilege lacking any constitutional overtones of the separation of powers, whereas the chief executive communications privilege is rooted in the constitutional principle of the separation of powers.

The chief issue addressed by this article is the state government officials adoption of the constitutionally granted right to the President of the United States in the Constitution. Many states, such as New Jersey, Maryland, Delaware and Virginia, claim that their governor’s responsibilities and communications are analogous to those of the President of the Unites States, and therefore his need for discretion in regards to documents disclosed is to be respected. These states typically utilize the balancing test, adopted from the US v. Nixon case, which weighs the qualified privilege of confidentiality against a sufficient showing of need by the party requesting the information. While executive privilege is recognized, it can be challenged viz a vie this test, and both the government official and the party requesting the documents have high burdens to meet.

Other states take a strict interpretation view of their governor’s right to exercise executive privilege. Kentucky, California and Vermont, for example, state that executive privilege protects the deliberative process as outlined by Chief Justice John Marshall in Marbury v. Madison. The perspective sees the judicial review of executive prerogatives as meddlesome, and see the privilege as required for the healthy exercise of the executive branch as distinguished in the Constitution.

Still other state governments, such as Massachusetts’, feel that there are no situations in which a state government official may draw parallels to the President of the United States. Massachusetts point blank rejected the recognition of executive privilege on the state level. This vantage point is well explain in the dissent of the Ohio case of State ex. Rel. Dann v. Taft states “the duties present in Article II for the President that require secrecy—national security and diplomacy—simply are not part of the governor of Ohio’s responsibilities. The executive communications privilege is unique to the President alone”. State ex. Rel. Dann v. Taft, 111 Ohio St.3d 1406 (2006); Matthew W. Warnock, Stifling Gubernatorial Secrecy: Application of Executive Privilege to State Executive Officials, 35 Cap. U.L. Rev. 983 (2007).

Once all perspectives and state examples are discussed, the article then turns to suggested tests for the utilization of executive privilege at the state level based on the balancing test that many states adopted from the federal courts. “This test pits the need for disclosure against the government’s interest in confidentiality. Upon a sufficient showing of need, the majority of the states require the court to conduct an in camera review”, which weighs the government’s need for confidentiality against the litigants need for protection. The author of the article then suggests amendments to this test so that it might be uniformly utilized across the states that recognize executive privilege.

Comparison & Analysis

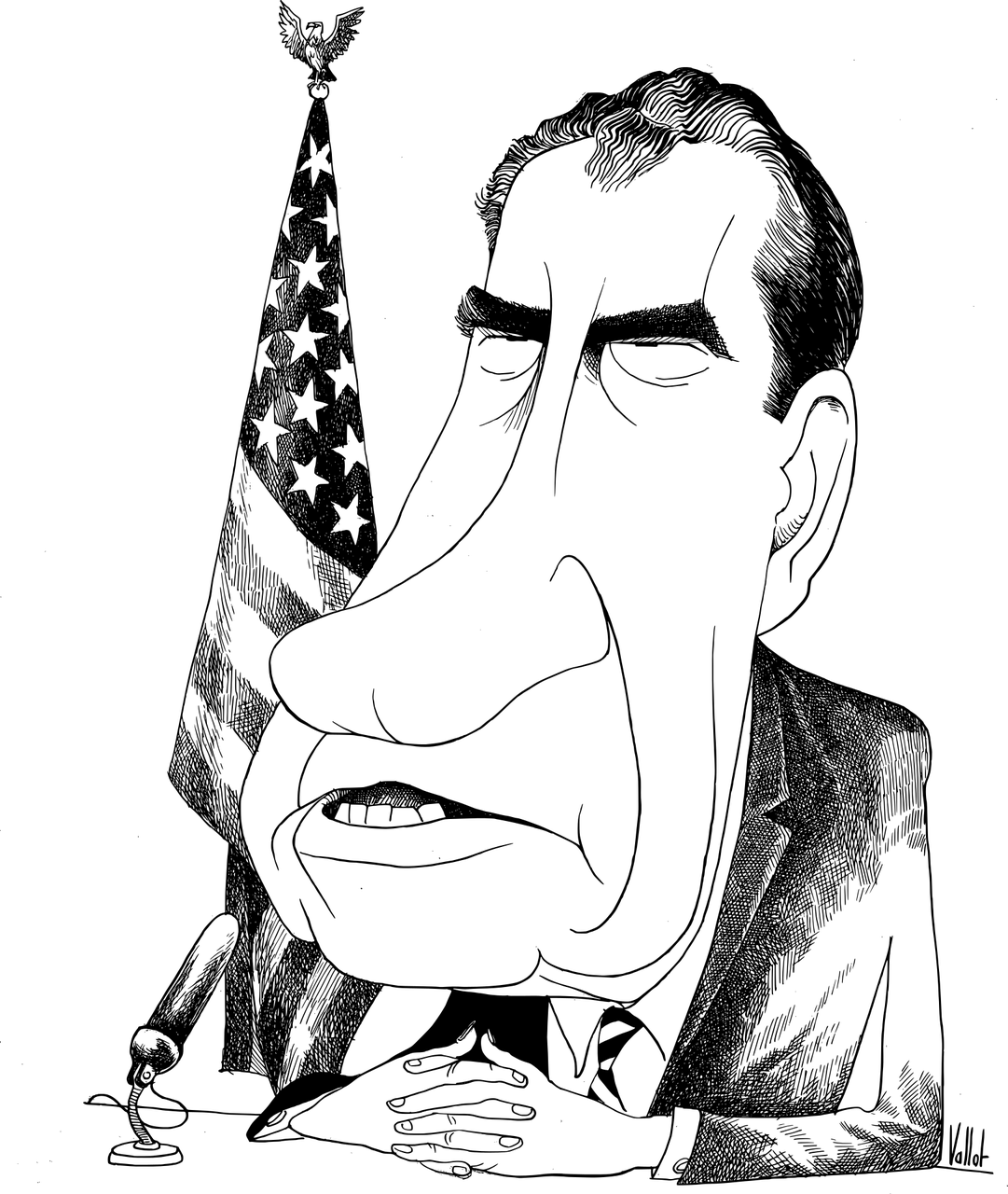

The discussion in Stifling Gubernatorial Secrecy: Application of Executive Privilege to State Executive Officials is focused around the utilization of executive privilege on a state, whereas the case of United States v. Richard M. Nixon, President of the United States, is a case regarding the use of the privilege in federal government. Executive privilege was asserted by Nixon in order to alleviate his duty to present recorded conversations as evidence to the special prosecutor in the Watergate scandal. The court ultimately held that “the Presidents generalized interest in confidentiality, unsupported by a claim of need to protect military, diplomatic or sensitive national security secrets, could not prevail against special prosecutor’s demonstrated, specific need for the tape recordings and documents.” United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683 (1974).

While Nixon argued that judicial review would interfere with decisions from the executive branch, the court ultimately stated that, absent a nationally sensitive issue, an unqualified executive privilege would interfere with the judiciary’s role, which would also be a separation of powers violation. In short, the judicial process may outweigh the president’s expectation of privacy. This is the basic foundation of the balancing test that many states have adopted in their local utilization of executive privilege. For example, in the New Jersey case of Nero v. Hyland, a governor was able to exercise executive privilege in refusing to disclose a background report. The court felt that it was more important to “protect the confidentiality of communications pertaining to the executive function” than it was to allow the release of a background investigatory report compiled for the nominees for the state lottery commission. The scale was literally tipped in the executive’s favor, hence the balancing test. This test is capable of tipping in the opposite direction, as we see with the holding in Nixon.

The Nixon court also clearly states that if executive privilege is to be exercised, there must be legitimate military, diplomatic or sensitive national security secrets. The aforementioned Ohio dissent said that this element precluded the states’ representatives from utilizing executive privilege, because these sensitive military & diplomatic situations are unique to the office of the President of the United States. It was, in fact, this lack of a situation that precluded Nixon from being able to use executive privilege in his criminal trial. However, a local governmental analogy can be drawn in some state situations. Take for example the state of New Mexico, which enforced executive privilege when the attorney general refused to hand over investigatory reports from riots in a state penitentiary. Matthew W. Warnock, Stifling Gubernatorial Secrecy: Application of Executive Privilege to State Executive Officials, 35 Cap. U.L. Rev. 983 (2007).This is the approximate state equivalent of a diplomatic and/ or military situation for the state, and therefore the communications between the attorney general and other members of the executive department were deemed to be privileged.

Not all state courts require such elements for executive privilege to be qualified. While “no state has been willing to take an unprecedented leap to declare the doctrine of executive privilege to be absolute”, Vermont did come dangerously close; while Vermont does utilize a balancing test to a minimal degree, the requesting party has a heavy burden if it wishes to be privy to the inner workings of the executive branch of the state government. Id. While policies vary from state to state, the majority of states require some burden to be met by both the party utilizing the executive privilege defense, as well as the party requesting the disclosure of the government information/ documentation, and then the court exercises an in camera review in order to determine which way the scale tips in the balancing test. While there are extremes like Vermont, which has almost absolute executive privilege, and Massachusetts, which does not recognize executive privilege on a state level at all, most of the states have followed the lead of the federal government and found some median version of the balance test to aid them in appropriately applying this privilege.

Current Issues

The exercise of executive privilege on a gubernatorial level is of great interest to me, especially due to the political climate of America today. While executive privilege is closely regulated by the checks and balances asserted within the structure of the federal government, the state government does not have such a powerful or public watchdog. When Nixon asserted executive privilege to withhold recordings from the special prosecutor ion the Watergate scandal, America knew. It was news; there were tapes in existence and Nixon didn’t feel it was America’s place to hear it. The Supreme Court examined the issue and ruled on it accordingly. While most state governments are modeled as mini-federal governments, with governors often sitting at the executive head of the table, local governments do not have the same opacity with the public that the country had in the U.S. v. Nixon trial. Governors would be able to assert executive privilege without as many checks as the federal government has. States like Vermont, that have minimal checks on their state executive privilege, exemplify this concern.

Conversely, the President must have the ability to “shield confidential, executive branch communications from disclosure”. Matthew W. Warnock, Stifling Gubernatorial Secrecy: Application of Executive Privilege to State Executive Officials, 35 Cap. U.L. Rev. 983 (2007). How can the President, as Commander and Chief, openly discuss an acceptable loss of American soldiers in war, when the mothers of those soldiers are listening to the conversation? This is an example of how executive level decisions may be tempered by a complete free flow of information and communications. The balancing test expressed in the Nixon case, shielding communications relating to sensitive diplomatic and military situations should hold and be enforced only across the executive branch of government. The state governments should not be able to exercise government privilege. The issues that affect the president, as the dissent in In State ex. Rel. Dann v. Taft expressed, do not occur within local governments to the same degree, and the risk of local corruption utilizing the use of this power is much higher. It is under this rationale, therefore, that the gubernatorial expression of executive privilege should be quashed.